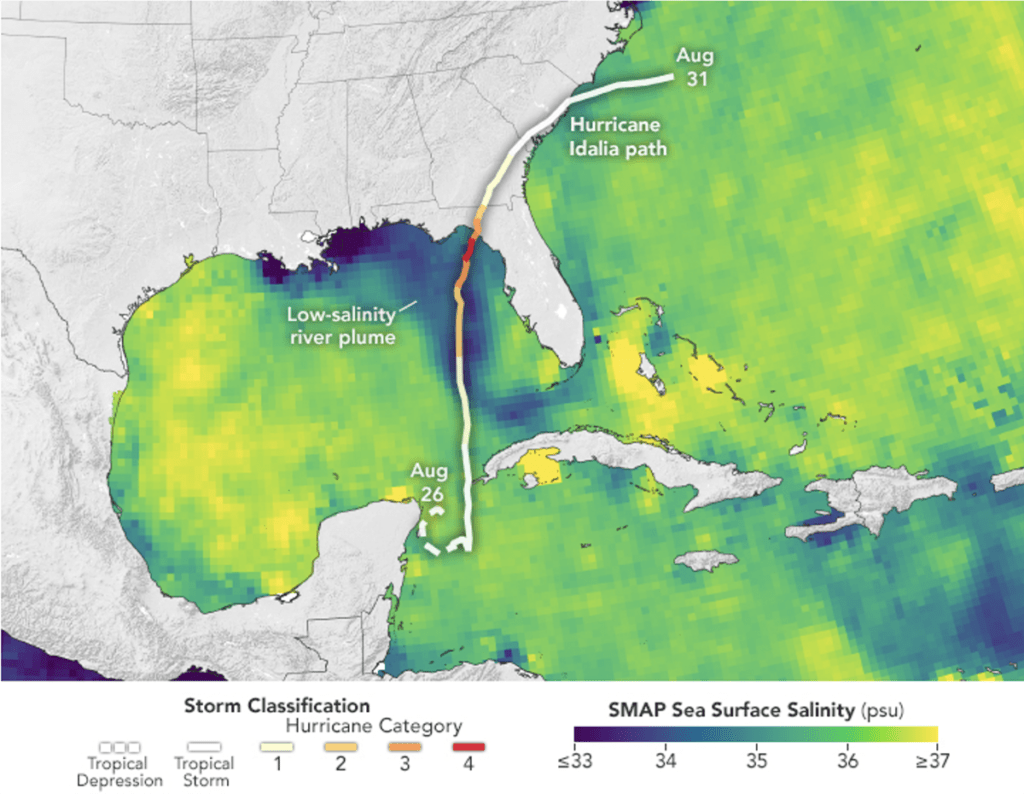

Hurricane Idalia rapidly intensified from a Category 1 to a Category 4 storm in under 24 hours before striking Florida’s Big Bend in August 2023—a phenomenon that’s becoming more common in the Gulf of America. Now, researchers at the University of South Florida’s St. Petersburg campus say freshwater from rivers may be playing a surprising role.

In a recent study, USF oceanography professor Chuanmin Hu and his colleagues found that river runoff can help trap heat near the ocean’s surface, creating conditions that accelerate storm intensification. The research team was investigating Gulf water quality using satellite and glider data when they noticed an unusually large freshwater plume stretching from the Mississippi River to the Florida Keys.

While ocean temperatures were at record highs in 2023, wind conditions during Idalia’s approach were not especially favorable for rapid storm development—prompting the team to dig deeper into other possible influences.

They discovered that the thick layer of low-salinity water from swollen rivers acted like a thermal lid, reducing ocean mixing and preventing cooler water from reaching the surface. This allowed more heat to remain at the top of the water column—prime fuel for hurricanes.

“We know river plumes are common,” Hu told the Catalyst. “But it’s rare to see them play such a major role in storm intensification. This was unexpected.”

The findings were published in Environmental Research Letters. The study included contributions from USF’s Optical Oceanography Lab, Ocean Technology Group, and the University of Miami.

Hu explained that typically, individual rivers don’t produce enough runoff to affect storms. But in Idalia’s case, multiple rivers combined to form a massive, long-lasting plume at the height of summer when Gulf waters were already abnormally warm.

Rapid intensification is defined as an increase of at least 35 mph in sustained winds over 24 hours. Normally, strong hurricane winds churn up cooler water from below, limiting storm strength. But during Idalia, the freshwater layer blocked this process, allowing the storm to gain power quickly.

Hu believes hurricane models should start factoring in freshwater plumes as a variable. Past studies have hinted at similar effects: a 2007 paper showed that over two-thirds of Category 5 hurricanes from 1960 to 2000 passed through large plumes from the Amazon and Orinoco Rivers.

Based on his team’s findings, Hu says a storm initially forecast as a Category 2 could reach Category 3 or 4 if it crosses a persistent freshwater plume. Still, he emphasized the importance of trusting meteorologists and watching forecast updates.

“A hurricane doesn’t go from Category 1 to 4 instantly,” he said. “People still have time to react if they’re paying attention.”

As for future concerns, Hu isn’t alarmed about a repeat scenario in 2025. “It takes the right combination—river flow, direction, timing, and an already warm Gulf,” he said. “But if those conditions align, a river plume could definitely make a storm worse.”

Follow the St. Pete-Clearwater Sun on Facebook, Instagram, Threads, Google, & X

(Image credit: NASA Earth Observatory)

PIE-Sun.com: local St. Pete-Clearwater news

Leave a comment