It’s not just Florida. Hurricane Helene inflicted widespread damage across other states. North Carolina was hit hard in particular. Some communities in the Tar Heel State. Much like the Sunshine State, the southern territory suffered enormous losses.

Sebastian Sarellano Paez was eating Cheerios when the floodwaters began rising around his family’s Swannanoa home. The 17-year-old forced himself to remain calm as two feet of murky water from Hurricane Helene surrounded their house. “My brain put itself into survival mode,” he recalls. “I wasn’t processing anything emotionally.”

Swannanoa, a working-class town that supplies much of nearby Asheville’s service workforce, was devastated by Helene. The storm’s fury particularly impacted the mobile home parks nestled precariously in mountain coves, leaving behind only rubble where houses once stood. For families like the Paez’s, who immigrated from Mexico years ago, the storm upended everything.

The destruction stretched far beyond Swannanoa. Hurricane Helene claimed over 200 lives—approximately half in North Carolina alone—and displaced hundreds of thousands. Twenty-seven North Carolina counties received major disaster declarations, with the governor’s office reporting over 70,000 damaged homes, many uninsured.

The Slow Burn of Collective Trauma

Mental health professionals warn that beneath the visible destruction lies a deeper crisis: collective trauma that could affect communities for years to come. The quality and accessibility of mental health care in the coming months will prove crucial for recovery.

For Sebastian, survival meant watching his own life unfold like a movie. He observed as his family’s desperate 911 calls went unanswered, as they fled through waist-deep water to a neighbor’s empty house, breaking in through a window—a decision that ultimately saved their lives. From there, they watched their own home disappear beneath the rising waters.

“I felt like I was standing at the gates,” Sebastian says of the moment he thought they might not survive. As water crept up the sides of their refuge, his mother Maria chanted prayers beside him. Sebastian closed his eyes, trying to focus on happy memories. Just then, his father noticed the water beginning to recede.

Building a Mental Health Response

Experts predict 20-40% of survivors may develop post-traumatic stress disorder, with symptoms potentially peaking months or years after the disaster. Tracy Hayes, who oversees state mental health services through Vaya Health, emphasizes the challenge: “It’s very hard for people to get better and to improve their mental health if they don’t have a safe place to live.”

The state has committed $25 million for mental health resources, supplemented by billions in federal aid approved in December. Initial response included crisis counselors at walk-in centers, but focus is shifting to building long-term mental health infrastructure.

For families like the Paez’s, now living with friends while rebuilding their gutted home, recovery comes step by step. Local organizations have mobilized to help, including LEAF Global Arts, whose executive director Jennifer Pickering has shifted focus from festival planning to disaster relief.

Ripple Effects Through the Community

The trauma extends beyond those directly displaced. Ann DuPre Rogers, a clinical social worker running Resources for Resilience, describes how the disaster has forced therapists to reimagine care delivery. Many survivors struggle with a newfound distrust of the land itself, particularly those who experienced landslides.

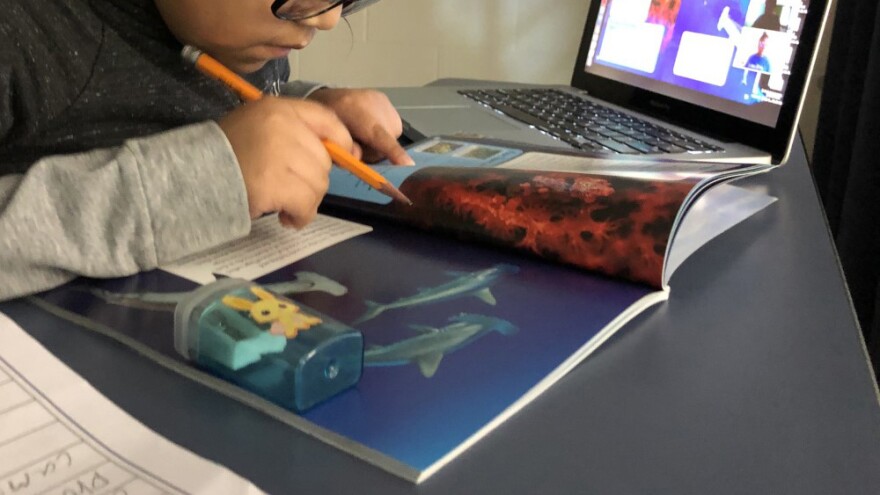

Children face unique challenges. Seven-year-old Diego Hernandez cries when it rains, begging his mother Maribel to take him somewhere safer. The North Carolina school system is investing millions in crisis support services, conducting statewide surveys to identify urgent needs.

For Sebastian, who recently turned 18, the experience has been transformative. “It’s horrifying how close you can get to not being able to see your loved ones again,” he reflects. Yet he’s emerged more mature and grateful for life’s experiences, both good and bad. As he applies to UNC-Chapel Hill, he’s not worried about choosing a major—he knows he has a lifetime ahead to decide.

Follow the St. Pete-Clearwater Sun on Facebook, Instagram, Threads, Google, & X

(Image credit: Mike Belleme/NPR)

Leave a comment